Content warning: This essay mentions physical and sexual abuse.

I have panic attacks. I remember when I had my first one that cold Michigan day while shoveling snow. I had no barrier to keep the wind out of my lungs, and my exertion welcomed a pulmonary assault that sent my mind on the greatest deception I had known. It made me believe I was going to lose my breath and collapse outside, and no one would know or care or come to help me. If you understand the nature of anxiety, you know how self-perpetuating she is.

I’ve come to realize that my anxiety is rooted in trauma, an enemy I have been acquainted with since birth. I actually can’t recall the day trauma moved in. It could have taken residence in utero when my 18-year-old mother traversed the streets of Harlem, New York, with a lead-poisoned toddler and me on the way. Maybe it was on the day of her subsequent death as her drug-addicted, diseased body lay under a sheet in the morgue at Harlem Hospital. That was the day I became an orphan.

That was also the day I learned that, even in my young, fragile state, no one would come for me. My first memory—I must have been three—is foster care with him. In the musty basement where the air was thick with a monster’s sweat and semen, where nobody came for me. Even as I told my tale to the powers that be, they sent me to that basement again and again. Foster care was not care but a four-inch strap to the back for responding “huh” instead of “yes,” and nobody came for me. I could have lost my breath, collapsed, and no one would have known or cared.

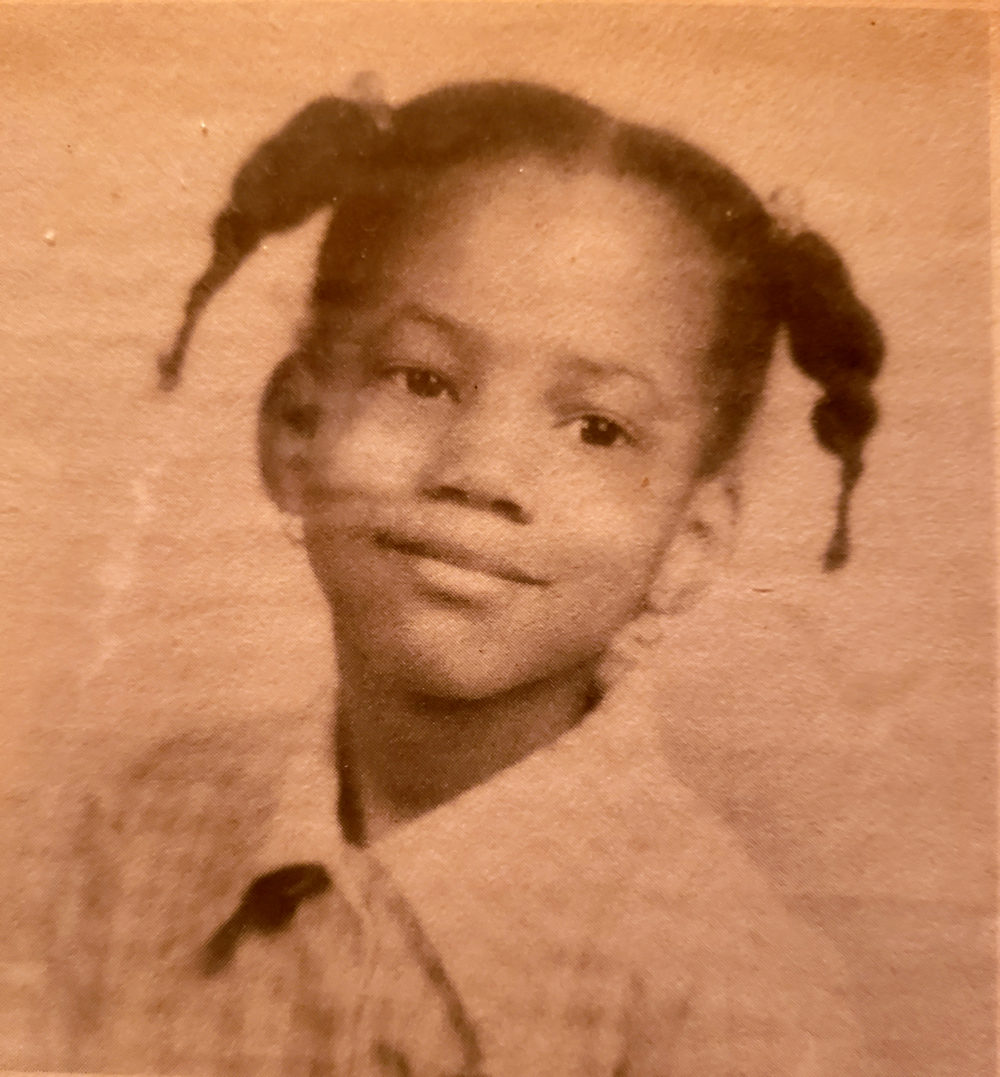

Denise Kingdom Grier as a child.

It took me years to feel like I wasn’t alone in being orphaned. Mephibosheth, whose story is told in 2 Samuel 9, was also an orphan. He was the son of Jonathan and the grandson of Israel’s first king, Saul. He had been born a child of war and had fallen victim to his father’s demise and the negligence of his caretaker, which rendered him both orphaned and physically disabled. He took up residence in Lo-debar, a forsaken place built by isolation and fortified by trauma. Lo-debar is wherever orphans are placed to hide their state, muffle their cries, and ensure that their one single truth is confirmed: If you collapse, no one will know or even care.

But, as I’ve learned, slowly, there are a few who care. One of those was King David. “Is there still anyone left of the house of Saul to whom I may show kindness for Jonathan’s sake?” asked David (2 Samuel 9:1). King David loved Jonathan and respected Saul, but even more, he had the heart of the God who destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah for their failure to provide for the most vulnerable among them, who placed Moses in the adopted family of Pharaoh’s daughter, who declared that the religion that is true and pure is one that cares for orphans. Indeed, God’s heart burns and aches for orphans—perhaps because their existence implies something about God that is untrue: That God does not come and God does not care for those who have no one else to come or care for them.

Is there anyone? the king demands to know. There is one. Jonathan’s little boy, Mephibosheth. He lives in Lo-debar, meaning “no pasture”—a desolate, desperate, forsaken place that seeps into one’s being and identity. Where I am is who I am: Lo-debar.

But David did what Jesus did when he saved us. The king himself went down to Lo-debar, met face to face with this destitute orphan, and told him, You will no longer live as one who is forgotten by humans and by God. From now on, you will eat at my table, which doesn’t just mean that you will never starve but that you will sit as one of my sons, adopted into the kingdom.

One day, this truth invaded the lie in my own life. An old childless wife had a dream, and in it, God showed her two children who were down in a sort of Lo-debar. God showed her two orphans and told her to adopt them. She and her husband scoured the myriads of books, full of faces of countless orphans lingering in their own Lo-debar-like places, until they saw the faces God had shown her in the dream—the faces of my brother and me. “These are the children God showed me in the dream,” she explained to the social worker.

The couple went down to Lo-debar—the place of trauma and abuse—and found my brother and me, five and seven years old. The family name was Kingdom, and ever since then I have been welcomed to sit at the Kingdom table as a daughter, an heir, a witness to the truth that God uses the arms of faithful believers to catch our collapsing spirits, to notice, and even to care with the heart of God.

Now, I live my life as a pastor and missionary who returns to Lo-debar to be a witness for orphaned and vulnerable children. I serve with Setshabelo Family and Child Services (SFCS), an organization in Botshabelo, South Africa, that is working to restore families in an area with tens of thousands of orphaned children. I know what it’s like to live in Lo-debar, so I’m that much more driven to proclaim good news to the children in that place now. God does come. God does care. God uses the arms of faithful believers to lead orphaned children to sit at the table in God’s kingdom forever.

Support Denise’s work with SFCS. This article was also published in RCA Today, the Reformed Church in America’s denominational magazine.

Rev. Dr. Denise Kingdom Grier

The Rev. Dr. Denise Kingdom Grier lives in Holland, Michigan, and is the mobilization pastor at Mars Hill Bible Church in Grandville and Grand Rapids, Michigan. She serves the Reformed Church in America as RCA Global Mission’s liaison to Setshabelo Family and Child Services in South Africa, where 30,000 orphans are finding loving homes within their community. She has been part of the RCA Women’s Transformation and Leadership guiding coalition since its inception and has helped give birth to Equity-Based Hospitality, Dismantling Racism, and the She is Called: Women of the Bible studies. Her work can be found at www.1cor13project.com.