I don’t really have heroes. I think maybe the world has become so divided that I haven’t found a ton to admire in the human race recently.

Actually, I do have one hero, though: my daughter Vika.

Vika came from Ukraine and into our family when she was ten. She was born with a condition called arthrogryposis, which, in her case meant she had club feet and couldn’t extend her knees past 90 degrees. In addition to that, somewhere along the line she picked up some neurological complications (we think it might have been from oxygen deprivation at birth—her non-bending knees might have made her birth an extended process). Anyway, she’s not well coordinated, can’t talk well, and has little balance.

Vika was abandoned at birth. She was put into an orphanage that was the worst of the worst. She remembers often being hungry. The kids were yelled at and smacked around and left to lie in their own pee. Some of the kids died. She wasn’t loved or cared for. The only thing people ever gave her was the strongest possible motive to resent other human beings. No one did anything to convince her that other humans might have something to offer.

Despite that depressing, oppressing existence, Vika survived. That inner strength alone shows astounding courage.

But it goes way beyond that. Not only did she survive—astonishingly, astoundingly, amazingly, inexplicably, she loves people. She’s warm. She smiles easily. She loves to laugh. She’s considerate and ever-grateful. Don’t get me wrong—she’s not perfect. I’d love to see a little more drive in her. But I don’t understand how, after everything that we humans have put her through, she can be such a positive, engaging person. That should have been ground out of her a long time ago.

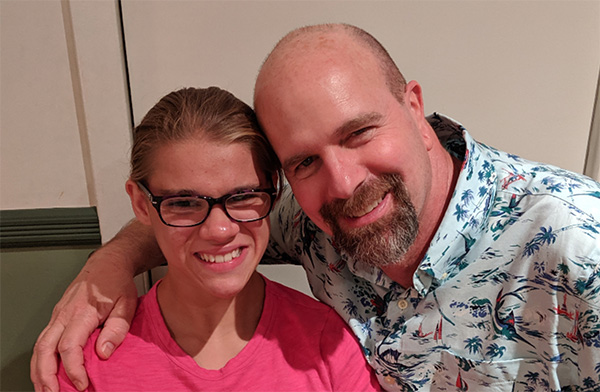

Steve Sayer and his daughter, Vika

That’s why I was so saddened yesterday. The eighth-graders in her school have been getting ready to go on a class trip to Boston. Four kids will share a room. Predictably, everybody picked their friends to room with, and the kid who doesn’t speak easily and is limited to a walker or wheelchair was left out in the cold, with no one to room with. And it hurts when you’re that kid. As a parent, there are no right words.

I’m not judging; I get it. I wasn’t all that sensitive when I was in junior and senior high, and am probably not all that sensitive now. I left a lot of “different” kids out in the cold. Most of us probably did.

You know, we do a lot of stuff these days to make life a little easier for folks who struggle with disabilities: ramps, elevators, redesigned bathrooms. But I bet that Vika would gladly climb four flights of stairs on her butt (that’s how she does it) if there were a couple of kids to room with when she goes to Boston. Or to hang out with after school. I bet there are a lot of folks out there who are challenged in some way or other who wish, more than anything else, for some friendship. A little authentic, non-patronizing conversation. A genuine relationship, maybe even outside the confines of all the programs we set up for people with special needs (as helpful as those programs are!). To be a little less lonely would change their world.

Here’s something I’m learning way too late in life. All the accommodations we make so people can enter a physical space make no difference if we can’t make accommodations in our hearts so that they can enter into conversations, relationships, and genuine friendships.

How do you make such space in the heart, though? It probably starts with remembering that most all people have something to offer. In relationships, there’s mutuality. We give a little and get a little. If a relationship with somebody else is all about us giving, it’s the very definition of patronizing. I can’t begin to tell you how much Vika gives me. She asks me how my day was, and she listens when I answer. Not that many people do. She’s the perfect outlet for my sophomoric humor. She laughs while my wife rolls her eyes. We like hanging out and just have a lot of fun together.

A person might have a little difficulty with speech. But they’re full of the same thoughts, emotions, opinions, and challenges that people with more agile tongues have. Those thoughts and emotions are fodder for a genuine, mutual relationship with any member of the human species, no matter their ability. Look for such things. Listen to them. You’ll be enriched.

There is a challenge in these relationships, though. A lot of times, you have to slow yourself down. Vika gets out one word per quick breath. There are some words she can’t pronounce really well, but with hand motions or alternate descriptions, she gets you to understand. It does mean that, if you’re going to have a conversation with her, you have to settle in for awhile. We’re used to life at 78 revolutions per minute. Vika operates at 33 1/3. (For those of you under the age of 50, that’s a vinyl record reference.)

Johnny Carson, who used to host The Tonight Show, once told a joke: What’s the shortest unit of time ever measured? The time between the light turning green and the guy behind you honking. That’s the world a lot of us operate in. Impatience. Go, go, go. Eating in the car on the way someplace. One of the best things we can do is to chill, let our heart rate get down to normal and show some patience. Patience is both the cost and the benefit of a conversation with Vika and a lot of other people.

There are a lot of folks out there—people with cerebral palsy, with Down syndrome, with dementia, or who’ve had a stroke—who require a little patience when we’re talking to them. They hope to receive it. And we’d be a little better off in the human department if we could offer it.

Jesus seemed to understand that. He was amazingly responsive to people with all kinds of different challenges. He hung out with people who were blind, who couldn’t walk very well, who had diseases or psychological disorders. The one that most stands out in my mind is Zacchaeus. Zacchaeus was, as the Sunday School song says, a “wee little man”—a short guy. Really, really short. As a tax collector, he did a job that made everybody avert their eyes or turn up their nose when he passed by on the sidewalk. And he cared so little about fitting in that he shunned convention and just shinnied up a tree in order to see Jesus when he strolled past. Zacchaeus was just … different.

Yet, when Jesus got near that tree, he looked up and shouted out, “Zacchaeus. Let’s have lunch.” Jesus spent time with folks that we’d consider different and he considered valuable. He set an example for how we are to be.

Look, realistically, we hang back from folks who seem different. We notice the differences between us more than the sameness. We worry about people glomming onto us and not letting go. We’re concerned about understanding folks when we talk to them … and so we don’t. Mostly, there’s something inside us homo sapiens that wants to simply be with people who are like us. It’s comfortable. And known. But instead of worrying about all that other stuff, Jesus just said, “Let’s have lunch. Let’s talk. Let’s get to know each other.”

Well, anyway, back to Vika. She’s had to overcome, or sometimes just learn to live with, challenge after challenge. Folks with special needs often have to be so indomitable. But it’s hard to be strong forever. I wonder: at some point, do depression and cynicism start to edge out warmth and friendliness? When you’re always alone, do you reach a point where you just give up?

There’s probably someone in your orbit who’s battling loneliness and wants to enter more fully into life. It’s not the most natural or easy thing to be that needed friend. Maybe we could be anyway. Jesus showed us that much of Christianity is made up of such small acts of love between people.

Steve Sayer

Steve Sayer is pastor of the Community Church in Harrington Park, New Jersey. He and his wife, Jeri, have seven kids, six of whom have been adopted out of difficult circumstances.