Some years ago, I served on the board of trustees of a college. The college chaplain was a feisty, firebrand kind of guy, always advocating for radical Christian discipleship. One of his projects was to organize small, share-and-prayer groups, and in that setting, students were invited to confess aloud their sins to one another. It was all voluntary; nobody was forced to participate. But a lot of students got involved, and before long, the board began hearing some hair-raising stories. Students were confessing sexual improprieties, cheating on exams, drug use. They were confessing things for which they could have been thrown out of school, arrested even.

The students liked the program. To them it was healing and humbling, a sharing of burdens, and an escape from the spiritual isolation that comes from unconfessed sin. It encouraged accountability and got students praying for one another.

Predictably, the board of trustees was aghast. We sat the chaplain down and told him to cease and desist. These young people were confessing things which could be ruinous to them. They didn’t realize what they were doing. This was just spiritual exhibitionism. We insisted he disband the program.

The groups were disbanded. The school year ended, students went home, the whole confess-your-sins movement blew over, and that was that.

But now, years later, I look back and wonder if we did the right thing. Here was a chaplain who was trying to create a community that would model the biblical ideal of believers confessing their sins to one another, and we made him stop. Why were we—why was I—so afraid of this?

Confession of sin is vertical, a matter between the penitent and God. But confession also has a horizontal dimension. It is one thing to say, in the Sunday prayer of confession, “God, forgive my sin.” It is quite another thing to confess that sin to another person, especially the person you have sinned against. “In the confession of concrete sins the old man dies a painful, shameful death before the eyes of a brother,” said the theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer. “Because this humiliation is so hard, we continually scheme to avoid it.”

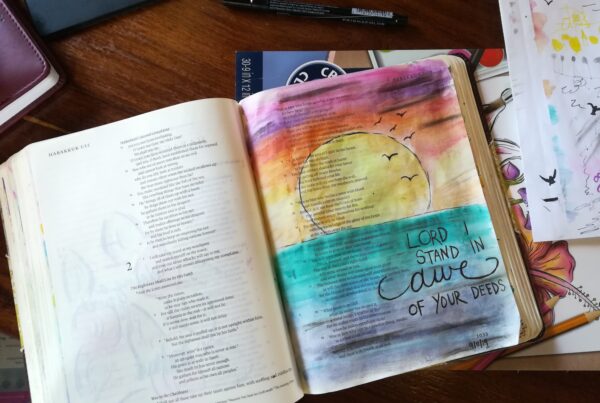

The Bible depicts a Christian community in which believers “confess your sins to one another, and pray for one another” (James 5:16). What would that kind of community look like—in a college, or a congregation, or a marriage? What if we not only confessed our misdeeds to God, but also, like the prodigal son, we went to the person we had wronged and spoke the shameful, painful truth: “I have sinned.”

Lou Lotz

Lou Lotz is a retired pastor who lives in Hudsonville, Michigan.