In this excerpt from chapter 3 of Creation Care Discipleship, Steven Bouma-Prediger describes one piece of holy ground and its holy creatures. The book as a whole reviews Scripture, theology, and ethics to uncover “why earthkeeping is an essential Christian practice.”

W ater and trees. Blue and green as far as the eye can see. A land of forest, lake, and stream. A labyrinth of water on the water planet. Such is the Quetico-Superior Wilderness of northeastern Minnesota and western Ontario. A canoe paddler’s paradise, this two-million-acre expanse of enchanted lakes, meandering rivers, and dense forest contains some of the oldest exposed rock on earth. With outcrops dated to three billion years ago, this ancient Precambrian bedrock, called the Canadian Shield, stretches in a vast arc from the Atlantic to the Arctic Sea across the upper part of North America. Walking on rock so old prompts you to marvel at the temporal scale of the natural world.

Imagine: Near your campsite is a large pond. On one end you see a dam, built by a colony of beavers. A marvel of engineering prowess, with sticks and logs and mud every which way, the dam is able to bear your weight and then some, even as it holds back the water. Not far from the dam you notice a large dome-shaped lodge. Twelve feet across and six feet high above the water, with two underwater entrances and walls four feet thick to keep the inner chamber free from predators such as the lynx and bobcat, and to keep it above freezing even in the coldest winter, the lodge is a snug and safe haven. As you quietly approach the lodge, you spot a beaver—black and brown fur glistening, long whiskers on dark nose, wide and flat tail—just before it dives underwater. Weighing in at up to sixty pounds, the beaver is the second-largest rodent in the world, after the South American capybara, and ranks second only to humans in its ability to deliberately alter its environment. With large front teeth that are, due to timber cutting, constantly resharpened, the beaver is capable of downing a three-inch-diameter aspen in thirty seconds. Such prodigious tree-cutting ability is a necessity when not only your shelter but your food is at stake, for the beaver is entirely vegetarian, preferring the bark of aspen and birch, as well as twigs and leaves. Though able to move on land, the beaver vastly prefers the water, and so its industrious dam-building serves to make available trees and vegetation that would otherwise be inaccessible. By flooding large areas, the average colony can more easily forage a large expanse for food.

While wading in the pond, your eye catches the zigzag pattern of water striders skittering across the surface. Buzzing just above the water is a dragonfly, its long body powered by two pairs of veined wings. As you exit the pond, you spot a leech. Four inches long and a half inch wide, with a gray-brown body, this wormlike bloodsucker evokes a near universal disdain. But leeches are an important part of the food web—providing nourishment for fish such as northern pike and walleye and also breaking down dead organic matter, thereby making crucial nutrients available to plants and all manner of aquatic organisms. Even the lowly leech has its role—its niche—in the functioning of the pond ecosystem.

As dusk falls, back at your campsite on a large island-studded lake, you hear the rhythmic “peep” of the spring peepers as well as the guitar-pluck “guunng” of the green frog along the water’s edge. Each male sings out to demarcate and defend his territory. You also observe the erratic flight of numerous little brown bats, flying low as they scoop in up to three hundred mosquitoes and other insects in a single hour. Without the maligned mosquito, these bats would be malnourished. Though not blind—contrary to what many believe—at night the bat must rely on his acute hearing to locate his prey. Using an amazing process called echolocation, bats send out ten to twenty high-pitched calls every second. Like underwater sonar, these sounds bounce off objects and return to the bat as echoes. Able to distinguish a flying beetle from a moth, the bat’s sense of hearing is incredibly acute and discriminating, as it must be if it is to survive.

Your reverie in observing bats is broken by a quavering sound—one of the haunting calls of that prototypical north woods bird, the common loon. The vibrato-like laugh you hear is the tremelo. Another loon, more distant, joins in, and you are serenaded with a tremelo duet. Just then you hear another of the loon’s four distinctive calls—the wail. This plaintive three-note call—long and mournful like the cry of the wolf—is a way of saying, “Where are you?” or, “Here I am.” On this night you hear a third distinctive loon cry—the yodel of the male. A complex chain of three to four three-part squeals, this call is used to attract a mate and defend territory. You now know where the expression “crazy as a loon” comes from. Only the quiet “hoot” eludes your listening ears on this night.

Of all the creatures of the north woods, by common consent the most alluring is not the moose, the black bear, or the gray wolf but rather the common loon. Big birds with a wingspan of about five feet, weighing up to fifteen pounds and marked by a jet black head, red eyes, white plumage, and a long sharp bill, the loon is easy to recognize. Loons are built for swimming and diving. They have been taken in fishing nets dropped to a depth of 240 feet. Their bodies are streamlined, with legs far to the rear for effective padding, and their red eyes allow them to see more clearly underwater. These birds do not have hollow bones, as some other birds do, but their bones are solid, thus giving them a low-in-the-water look and the ability to dive to great depths. Able to stay underwater for up to fifteen minutes, loons swim fast enough to catch game fish such as trout and perch, spearing their prey with their beak and then, after surfacing, swallowing it whole. Being built for diving makes flying more difficult, but loons are, in fact, powerful fliers. Requiring as much as one hundred yards before they can get airborne, once in wing the loon cruises at 75 mph and has been clocked as fast as 100 mph. The common loon is an unforgettable inhabitant native to this place.

On your leisurely walk from the pond back to your lakeshore campsite, you travel through a forest of balsam fir and white spruce, with some northern white cedar near the water’s edge. No birches or aspens stand among these conifers, for the forest through which you walk is a fine example of a climax boreal forest. Sometimes nicknamed “the spruce-moose forest,” the boreal forest circles the earth, for it is found not only in the northern climes of North America but also in Finland, Ukraine, and northern China. As you walk you see many balsam fir, with their famously fragrant needles, as well as pyramidal, Christmas-tree-like spruce here and there. Near the shore is the ubiquitous white cedar, with its scaly needles and peeling bark. You wonder why all the cedar branches are the same height and then remember that deer browse on the cedar in the winter. The lowest level of these branches represents the highest reach of the hungry deer.

Darkness settles in, like a gentle friend blanketing the land. With a new moon the stars blaze back at you brighter than you have ever seen them. Canis Major and Canis Minor, Draco, Cassiopeia, Cephas, Lyra, Cygnus, Aquila— these constellations and many more in all their stellar glory. And then, out of the corner of one eye, you see a weird dancing light just over the horizon. After a few seconds you realize you are witnessing the famed aurora borealis, or northern lights. Sigurd Olson tries to describe the indescribable:

The lights of the aurora moved and shifted over the horizon. Sometimes there were shafts of yellow tinged with green, then masses of evanescence that moved from east to west and back again. Great streamers of bluish white zigzagged like a tremendous trembling curtain from one end of the sky to the other. Streaks of yellow and orange and red shimmered along the flowing borders. Never for a moment were they still, fading until they were almost completely gone, only to dance forth again in renewed splendor with infinite combinations and startling patterns of design.

Caused by great solar flares that traverse the ninety-three million miles from our star to our home planet and enter the earth’s magnetic field, the northern lights are perhaps the most beautiful reminder that, in the words of a poem whose author I have long forgotten, “though things near and distant are, they are connected from afar.”

I hope this description of a small piece of the natural world evokes awe of our home planet and its Maker and provides one bit of evidence that our home is holy. In Scripture and in church traditions we find evidence of another kind regarding the holiness of the earth, but I think we must see it with our eyes and feel it in our gut to fully realize that this place we call home is a holy place. The earth is sacred ground.

Content taken from Creation Care Discipleship by Steven Bouma-Prediger, ©2023. Used by permission of Baker Academic.

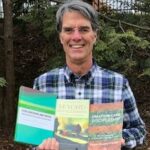

Dr. Steven Bouma-Prediger

Dr. Steven Bouma-Prediger is Professor of Religion at Hope College, where he has taught for the last 30 years. He is a graduate of Hope College, with a major in mathematics and computer science, and has master's degrees from the Institute for Christian Studies (in philosophy) and Fuller Theological Seminary (in theology) as well as a Ph.D. in religious studies from The University of Chicago. Prof. Bouma-Prediger has published over 100 articles and has authored eight books. He is married to Celaine Bouma-Prediger, an ordained minister in the Reformed Church in America and a marriage and family therapist, and they have three daughters.